Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and the Crystal Palace Prehistoric Animals

In the middle of the 19th century life-size sculptures of large to giant extinct animals of the Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras created by the English sculptor and natural history artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807 to 1889) were arranged in the Crystal Palace Park, Sydenham, South London, for the world’s first prehistoric park (LAMBRECHT & QUENSTEDT 1938).

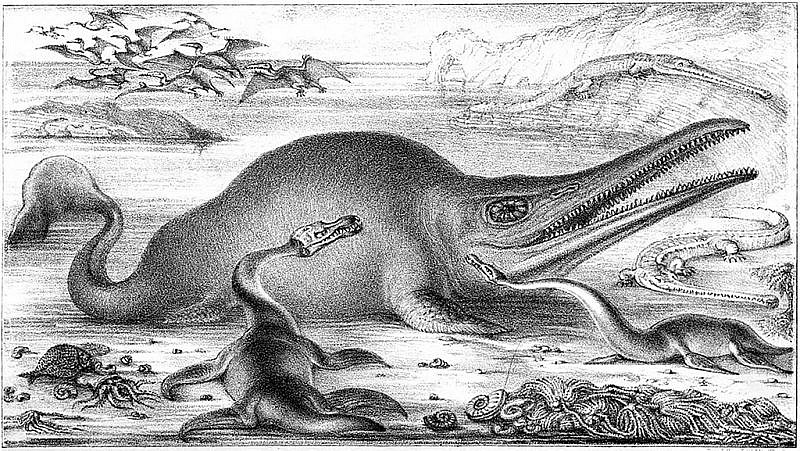

The diagram above with some of the reconstructed Paleozoic and Mesozoic taxa drawn by Hawkins in 1854 gives a good impression of the spectacular outdoor scene of vanished creatures established for the Victorian visitors (HAWKINS 1854: 446). With the reconstruction and display of these beasts at the time, controversial theory was introduced that such animals once roamed the earth. It predated Charles Darwin’s «The origin of species», which was first published in 1859.

How the Idea of the first Prehistoric Park was born

After the end of the 1851 London Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, Joseph Paxton’s glass structure – which had housed the fair –, commonly refferred to as «The Crystal Palace», was bit by bit moved from Hyde Park to Sydenham, where it was used as a permanent showcase for the arts and sciences. It seems that Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, was the first who suggested that the Crystal Palace should be adorned with restored beasts of the past at its new location.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins took over the task and started to construct statues of large mammals like the mastodon. Then he became aware of the monographs on the giant reptiles of the Mesozoic by Richard Owen, the superintendent of the Natural History Department of the British Museum. Instead Hawkins resolved to restore these creatures to their former glory and worked closely with Owen from the planning to the modelling phase.

The Crystal Palace was completely destroyed by fire in 1936 but the life-size reconstructions of the prehistoric animals are still preserved and can be visited until today. They are distributed across three islands as well as an artificial lake on the palace grounds (DESMOND 1975, MCCARTHY & GILBERT 1994). Additional background information on Hawkins’ historical sculptures in natural size, their conservation and where they are to be found in London can be looked up here > Friends of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

Table Models and PALAEOLOVE Replicas

Soon after the opening of the prehistoric park in 1854 nice table models were prepared from some of the Crystal Palace original beasts and sold worldwide in the second half of the 19th century by, e.g., Arthur Éloffe, Paris, and Henry A. Ward, Rochester, USA. For contemporary information on these small replicas see ÉLOFFE (1862) and WARD (1866). For more information on the sellers read the publications on Arthur Éloffe and Henry A. Ward in this blog. After MCCARTHY & GILBERT (1994: 25), the small-scale models were produced by Hawkins as «spin-offs» from his Chrystal Palace work. Today these fascinating historical models with their special appeal are very rare and can almost only be found, e.g., at auctions. PALAEOLOVE closes this gap and makes them – as replicas – again available to all enthusiasts of the creatures of the prehistoric world (Paleozoic and Mesozoic) as well as the palaeontological research history.

Finally it should be pointed out that in Appendix A of the publication by MCCARTHY & GILBERT (1994) yet another distributor of the table models is mentioned. According to these authors James Tennant (1808 to 1881), Professor of Mineralogy at King’s College, London, and official «Mineralogist to her Majesty the Queen», also intended to sell small models of Hawkins’ outdoor beasts in his shop at 149 Strand, London. Following a notification by Tennant himself these special models prepared for casting by Hawkins will demonstrate «… the anatomy as shown in the fossils on one side, while the other will present an entire restoration of those extraordinary British animals» (cited in MCCARTHY & GILBERT 1994: 91) [remark by PALAEOLOVE: in our opinion special table models with two different sides are unknown].

First Update (7 June 2016)

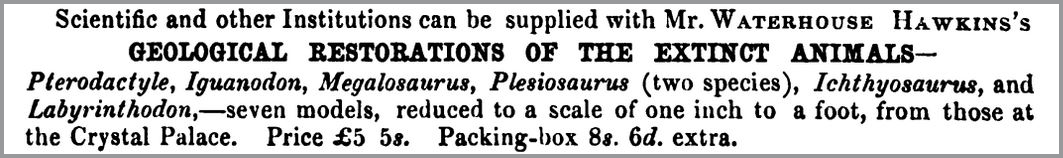

In a post elsewhere by Rohan Long written on 26 May 2016 we learn that James Tennant struck an agreement with Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to produce small-scale models of the dinosaurs Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, the aquatic reptiles Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus (combined as a tableau), the pterosaur Pterodactylus and «Labyrinthodon», an obsolete name for the temnospondyl amphibian Mastodonsaurus. In addition to these models, table-sized replicas were made by Henry A. Ward. The model types by Ward and Hawkins are very similar in their shapes but there are differences in their colouration. Ward’s models [remark by PALAEOLOVE: possibly sold by Tennant?] have a coppery-brown colour and a green plaster underside. Hawkins’ originals are painted in glossy black, while the exposed plaster underside is a mottled white, grey and green [this statement is the base for PALAEOLOVE’s Hawkins Style colouration].

Second Update (10. June 2016)

The small-scale models sold by Arthur Éloffe are also similiar in shape to the ones distributed by Ward and Hawkins. The colouration of Éloffe’s table models resembles the one of Ward’s replicas [an observation made by the PALAEOLOVE team and the base for PALAEOLOVE’s Éloffe Style colouration].

Third Update (19 July 2016)

Simon Jackson speculates in a post elsewhere written on 27 August 2014 that Hawkins prepared miniature-scaled models to present them to Owen, in order to seek scientific approval before creating larger-scaled statues. To support his view he pictures a greenish-reddish dyed plaster cast of an original Labyrinthodon table model shown at the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution.

Fourth Update (20 July 2016)

Tennant actually sold table models of Hawkins’ Crystal Palace reconstructions of extinct animals. These were probably the black ones already mentioned and they were most likely made by Hawkins. Compare the detail below from the extensive sales catalogue-like advertisement published by Tennant as appendix in BUCKLAND (1858).

Fifth Update (24 July 2016)

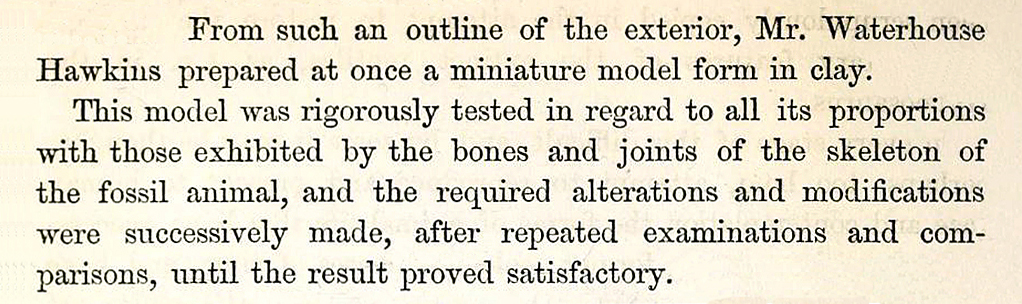

Hawkins indeed prepared miniature-scaled models and presented them to Owen before the erection of the life-size Crystal Palace reconstructions of extinct prehistoric animals as one can read in a paper published by Owen himself in PHILLIPS et al. (1854). See excerpt below.

DESMOND, A.J. (1975): The hot-blooded dinosaurs. A revolution in palaeontology, 238 pp.

ÉLOFFE, A. (1862): L’art de préparer les plantes terrestres, d’eau douce et marines pour en former des herbiers et albums pour l’etude, 38 pp.; with an appendix: Extrait du Catalogue de la Maison Arthur Éloffe, Rue de l’Ecole-de-Médecine, 20, Paris, 15 pp.

HAWKINS, B.W. (1854): On visual education as applied to geology, illustrated by diagrams and models of the geological restorations at the Crystal Palace. – Journal of the Society of Arts, 2 (78): 444-449.

LAMBRECHT, W. & QUENSTEDT, A. (1938): Palaeontologi. Catalogus bio-bibliographicus. – Fossilium Catalogus, Animalia, Ed. W. Quenstedt 72: 191.

MCCARTHY, S. & GILBERT, M. (1994): The Crystal Palace dinosaurs: The story of the world’s first prehistoric sculptures. The Crystal Palace Foundation, London, 99 pp.

PHILLIPS, S. et al. (1854): The palace and park: its natural history, and its portrait gallery, together with a description of the Pompeian Court, > 165 pp.

WARD, H.A. (1866): Catalogue of casts of fossils from the principal museums of Europe and America with short descriptions and illustrations, 228 pp.